BY JOANNE MATTERA

What does it mean, exactly, to curate an art exhibition? Curating is realizing a vision by means of the art of others, each work advancing the curatorial thesis with depth and breadth. Here’s a good working description of the process by Mary Birmingham, now chief curator at the Visual Art Center of New Jersey in Summit, but at the time of our conversation, curator at the Hunterdon Art Museum in Clinton, New Jersey: “Something stimulates my thinking. Then I start collecting names, which connect to other names. Studio visits follow each round of discoveries until the show develops.”

Since I do a fair bit of curating and have worked with both gallerists and museum curators over the past decade, I’d like to share some of what I have come to know. The examples that follow are illustrated with links to exhibitions I have curated or been involved with. This is not for self aggrandizement—I do plenty of that on my own blog and Facebook pages and don’t need to do that here—but to offer clear and accessible working examples of the ideas I posit.

Panoramic view of “A Few Conversations About Color”, my curatorial effort for dm contemporary gallery, New York City, January-February 2015. I wanted to assemble a visual colloquy with the work of a number of artists working in a variety of mediums, all of which engaged color as a primary element. From left: Nancy Natale, Joanne Freeman (in far gallery), Matthew Langley, Ruth Hiller, Julie Karabenick, myself. Photo: the author

There are different kinds of curators

Let’s look at the hierarchy of curatorial activity. Typically, museum curators are at the top and artist curators are at the bottom, but with a big-name artist and a small-town museum, that hierarchy would be inverted, so let’s just say that the field of curating is open to many in the art community working at all levels.

Museum curators work for or within an institution. They select themes and artists. To that end, they look locally at open studios, travel to nearby major cities to view exhibitions and events, and annually visit a few art fairs farther afield—New York City, Miami, Los Angeles, maybe Havana, London, Istanbul or elsewhere around the globe—to see what’s out there. While curators at this level have autonomy, they work within the mandate of the museum, whether it’s to embrace art and science, for instance, or to focus on the work of a particular region.

Gallerists curate their own gallery exhibitions. While most don’t typically identify each exhibition as having been “curated by” themselves, the understanding is that a good gallerist is in fact always curating the selection of works that go onto the gallery walls. Occasionally a gallerist will curate for an institution, in which case she would be identified as curator.

Freelance curators may be artists, but often they are entrepreneurs who manage a variety of art-related projects: curating, consulting, private dealing. All are deeply involved in the arts community, seeking, finding and organizing sometimes large numbers of artists, as museum curators do, but typically on a smaller financial scale. A freelance curator operating in a large city such as New York City, might create exhibitions for the lobby of a corporate client (a financial institution, say) or an academic gallery, or perhaps for a commercial gallery. Freelance curators get paid.

Artist curators are newly legitimate. Though there is a long history of artists running galleries—think Alfred Stieglitz and his American Place gallery in New York City in the Thirties, and the genre of artist-run co-op galleries in which artists handle everything from curating exhibitions to sweeping the floor—it is only fairly recently that individual artists have begun to curate on a regular basis and to be respected for the work they do. Some museum curators may look askance at artist curators in much the same way that professional artists might look at Sunday painters—do it, enjoy it, but you’re not in the same league—while others embrace the fresh point of view that artists bring to curating.

A good example of the kind of exhibition that can come as a result of open lines of curatorial energy is the exhibition Doppler Shift, curated by Mary Birmingham for the Visual Art Center of New Jersey in 2014. While the exhibition is Birmingham’s own curatorial effort, the initial concept was developed by artist Mel Prest, who took a small traveling version of the show (the work fit into a suitcase) around Europe several years earlier. ProWax member Debra Ramsay introduced Birmingham to an iteration of Prest’s show in Brooklyn. With Prest’s consent, Birmingham grew it into a multi-gallery effort at her museum.

Installation view of “Doppler Shift” at the Visual Art Center of New Jersey, curated by Mary Birmingham from a concept and early exhibition developed by artist Mel Prest. Photo: Guido Winkler

Most artist curators work for free, curating being an extension of our practice. But I say, if you do the job, ask for payment. It might be a flat fee—anything from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand—or a percentage of sales. Artist curators are typically active in many art communities, and a good artist curator will bring together members of several communities in service to a vision. Indeed, creating community is one of the reasons I curate. One thing artist curators need to guard against is becoming known for putting themselves in every show they curate. Sure, sometimes we include our work, but if that’s the only way we get to show—the community notices—we undercut our own best interests.

What does a curator do?

Now that we understand some of the basic kinds of curators there are, let’s look at what the curator does.

A curator has a vision. A curator conceives and develops an idea for an exhibition. Ideally, the idea is fresh, but even a conventional theme can be infused with new thinking. After much consideration she selects the work, choosing so that each piece illuminates some aspect of the  exhibition theme. Typically, the planning for a curated exhibition will take ten times longer than the run of the show. Studio visits alone are demanding of a curator’s time, and there’s a lot of thinking about how everything she is seeing might come together in a cohesive, well-selected whole.

exhibition theme. Typically, the planning for a curated exhibition will take ten times longer than the run of the show. Studio visits alone are demanding of a curator’s time, and there’s a lot of thinking about how everything she is seeing might come together in a cohesive, well-selected whole.

When the artists have been selected but the work has not—that is, when a person brings together a selected group of artists but leaves the selection of work up to the artists themselves, we call the show organized by rather than curated by.

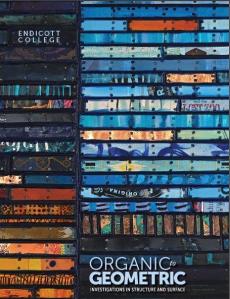

Installation view of Organic to Geometric: Investigations in Structure and Surface, curated by Carol Pelletier for Endicott College, where Carol is Chair of Fine Arts and Professor of Art. From left: Dawna Bemis, Paul Rinaldi, Howard Hersh, Nancy Natale; foreground, Susan Lasch Krevitt. Carol’s idea was to bring together artists working in encaustic without the result being an “encaustic show.” To that end she developed a working theme, perfectly described by the title, and selected work to sustain and amplify it.

Photo: Michael Miller

A curator typically writes a statement. The visual result of the curator’s (or organizer’s) thesis is the exhibition itself, but a statement allows the viewer to understand more fully what the show is about and why the curator selected the artists she did. A statement might be a short wall text or printed handout. Going a bit further, the text might state the thesis of the show and then discuss each artist’s work. Going yet further, the text might include an image from each artist so that those not visiting the show itself show would see how the curatorial concept came together.

Ideally, the curator produces a document with more heft than a handout because it allows the exhibition to have a life beyond the dates of the show and be available for reference. Brochures, catalogs, websites, or blog posts are all good options, depending on your time and money budget. Given print-on-demand options, the catalog could exist as a document online (ideally, free for viewing) as well as being available for sale as a print book.

As an example, here’s the catalog, designed by ProWax member Ruth Hiller, which I conceived for the exhibition A Few Conversations About Color at dm contemporary in New York City in January-February 2015. Print-on-demand catalogs are a great way to get a good catalog without spending a lot of money upfront.

The catalog for A Few Conversations About Color, organized by me and designed by Ruth Hiller. My essay provides context for the artists, each of whom is represented with a statement and four pages of images, viewable online by clicking image

I had been hesitant to go the print-on-demand route until I started to see galleries publishing such catalogs. Indeed, even museums now publish this way. Here’s Doppler Effect produced by Mary Birmingham for the Visual Art Center of New Jersey. With institutional funding behind her, Birmingham was able to hire an essayist to complement her own curatorial essay and produce a large enough print run to give each artist multiple copies of the catalog. It’s also online and will remain so, allowing the exhibition to exist in cyberspace forever.

Another wonderful example is Organic to Geometric: Investigations in Structure and Surface, curated by ProWax member Carol Pelletier for Endicott College in Beverly, Mass. Designed by ProWax member Karen Freedman, it features a foreword by the curator, who secured professional installation photography, and a spread for each of the 19 invited artists.

The catalog for Organic to Geometric, designed by Karen Freedman, with a curator’s foreword by Carol Pelletier and an essay by me, viewable online by clicking image

When circumstances do not allow, consider a dedicated blog. With the permission of the curator and participating artists, I created a dedicated blog for Formal Aspects, a five-artist exhibition at the Cape Cod Museum of Art in 2015. If you’re the curator, check with the institution to see if there’s any specific information about the venue that should be included.

If you are curating

• A compelling theme or thesis is the foundation of a strong show

• Come up with an evocative title that conveys your intent

• It’s not enough to secure the venue; consider the physical infrastructure. Is the space set up for an exhibition? Is there access to deliver work? Is there parking?

• Consider the administrative infrastructure. One of the great things about curating for a gallery or museum is that administrative help is available. If you’re curating in a pop-up space, you’re on your own administratively—and it’s a daunting job

• If you’re putting out a call to artists, state all the information up front: who, what, where, when. If artists will be asked to contribute financially to the exhibition, or if they will be expected to cover the cost of shipping their work one or both ways, note that. Be clear about what you’re looking for thematically

• Don’t be afraid to say no. You are the curator. You don’t need to justify your selections

• It is, however, important to remember that artists have opened their studios to you. If you do not plan to include their work, let them know in a timely manner. They may have other projects for the work that had been under consideration

• Once you’ve made your selections, create a reference document that each selected artist can refer to so that you’re not inundated with calls asking about delivery, opening dates and such

• Produce a press release that you distribute to the various media outlets. State the name of the show, the name of the curator, dates, location, hours of the exhibition. Include a short description of the show and a list of exhibiting artists. Media are likely to include a photo or photos if you provide them.

• Provide a copy of the press release to each of your artists, who will be creating their own posts and newsletters to promote the event

• Be clear to your artists that press requests should go through you. This is your curatorial project. You don’t want an artist creating her own press materials to make it sound as if she’s in a solo show, nor do you want the press to focus on one artist

• Additionally, you might create a list of talking points to enable your artists to describe the show cogently and accurately (helpful if they are being interviewed)

• If you cave to pressure to include your friends, even if their work is not right (or not good enough), you are not a curator, you are a wimp

• If you’re working with juried work, you are not a curator. You’re an organizer. Understand the difference. You will still have many or most of the responsibilities previously stated, but without having selected the work, you cannot claim the title of curator (well, you could, but you’ll look like an amateur)

• You’re going to put in a lot of time to conceptualize and curate a show. Select a venue that’s worthy of the effort and the art. Coffee shops, bakeries, laundromats and the like are not worthy of professional effort

• Can’t find the right bricks-and-mortar space? Curate an online exhibition. Online curating—on your blog or in a dedicated website—can be a great way to hone your curatorial thinking, and it’s a mitzvah for the art community, which never has enough visibility

If you are invited to be in a curated show

• Do you know the curator? If not, do your due diligence. Do a Google search, ask your artist friends if they are familiar with the curator or the institution. You want to be part of a project that advances your career and brings something to the community

• Is the show one of those hybrids, which seem to be popular in some parts of the encaustic community, that includes invited artists as well as a juried show? Vet it carefully. As an invited artist you are there to make sure the quality of the show is high. But if the juried entries aren’t good, you could be embarrassed by your inclusion. If you’re submitting to the juried segment, know that other artists have been brought in as invited guests, paying no fee. You’re the worker bee

• Is the show one of those hybrids, which seem to be popular in some parts of the encaustic community, that includes invited artists as well as a juried show? Vet it carefully. As an invited artist you are there to make sure the quality of the show is high. But if the juried entries aren’t good, you could be embarrassed by your inclusion. If you’re submitting to the juried segment, know that other artists have been brought in as invited guests, paying no fee. You’re the worker bee

• What’s the title of the show? If it’s yet another “Encaustic Art” of “Wax” show, you will not be served well. Look for themes that go beyond medium, a great way to broaden your professional visibility

. Ask “Who else have you invited? Who else will be in the show?” The two questions are not the same. You want to know who has turned down the invitation as well as who has accepted. If the artists you respect have turned down the invitation, you might contact them to inquire why. Most artists are willing to share this kind of information if you promise confidentiality—and keep that promise

• Priorities change. The exhibition you might have said yes to when you were just starting out may not be the one you want to be in now

• Ask: “How do you envision the installation? How big is the venue?” You labor to make good work. Assuming you are beyond the beginner stage, you owe it to yourself to place your work in the best possible light, both metaphorically and physically. The last thing you want is to be in a poorly lit, overhung show

• You want to be in a show that lifts you up with good work by good artists, not drag you down with the inclusion of hobbyists eager for an opportunity to show

• Respect the curator. Include her/his name in the exhibitions listing on your resume

• If you are contacted by the press, refer requests to the curator

• Remember: You are the lucky recipient of an invitation to show in an exhibition for which you will do none of the heavy lifting. That’s a gift!

So, should you curate?

If you have a great idea that you know you can realize with the very best work of the very best artists available to you, if you are well organized, and if you are willing to work harder than you can possibly imagine, then yes. Curating is a wonderful way to be part of something beyond your studio practice. Done well, your curatorial effort is a gift to the community. You enhance your visibility in the art world with an exhibition that in turn enhances the visibility of each featured artist. But done badly, it’s the very opposite of everything I just said.

Joanne, this is the most comprehensive writing about a topic that should be thought about a long time by anyone who considers curating a show/exhibit. I will have to re-read a. Umber of times even though I do not plan to curate a show. It gives me insight into what a curator should be doing.

So informative and smart, and so generous and thorough. Thank you Joanne.

Thank you Joanne for your generosity on this subject. I’ve been thinking of curating a show and this is invaluable information for me or anyone planning the same. I have just finished printing this article out for my files!

Thank you Joanne for sharing this valuable information! I’ve been thinking of curating a show and have just printed this out for my reference.