by Nancy Natale

The Abstract Expressionist movement occurred decades ago, popularizing the idea that spontaneity, improvisation, and process should be the guides in creating art. This kind of expression worked for trained painters such as Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, and Joan Mitchell, who approached their canvases with an understanding of color theory, composition, materials, and art history.

Today, many beginning artists seem to have adopted the view that medium and process will generate paintings for them without giving any additional thought to what they might want the work to mean. This notion is particularly prevalent with artists using the medium of encaustic. What generally happens is that they concentrate on effects produced by various techniques or processes achieved with the medium. Although good resolutions may be produced with some individual pieces, such medium-driven works are usually not very interesting over the long term except as sample boards.

Misunderstanding the Way Intention Shapes Art

I have observed that some beginning artists, particularly those who come to art making with no formal training, misunderstand what it means to use a more intentional approach to creating art. They fear that an intention must be so fully formed and strictly adhered to that it will eliminate the joy of creative discovery and the feeling of being in that zone that we all strive to find. Alternatively, if they do decide to use an idea to make a work, the idea is often so personal and idiosyncratic that it requires explanation for viewers to understand what the artist is attempting to depict. In such works, the specificity of the idea prevents the viewer from finding any universal meaning in the work. Some artists even go so far in carrying out their particular idea that they actually label the work with their meaning so that it becomes trite. We have all seen paintings that include clocks labeled with something like, “It’s about time.” Such a limited idea with or without labeling prevents viewers from finding interest in the work.

Intention Shapes Meaning

Creating with intention produces meaning in the work, and meaning in art exists for the artist and for the viewer. The meaning that each sees in the work may not necessarily be the same for both. The artist, of course, has a much more intimate relationship with the work, having created it, but the artist can’t always be sure how viewers will interpret the work. A knowledgeable viewer may find meaning in the work that the artist had not intended or that was overlooked by or hidden from the artist. This makes neither meaning “wrong” but only enriches the work. It’s another aspect of art that makes it so fascinating. To invite viewers to search for meaning, an artist must create work that allows a way in, that does not so direct the viewer to one meaning that it can be realized with a quick glance.

Is the Viewer Necessary?

There are some art theorists who posit that art is not complete without a viewer. Such a theory does not account for the sheer compulsion to create that drives those of us who make work for our own satisfaction, to answer questions or problems we pose to ourselves, or purely as a means of expression. There are always artists who are driven to create despite financial hardship or limited opportunities to exhibit. The creative urge takes many forms and art is not always made for others to find meaning in it. Sometimes it’s just enough for the artist to make his or her own meaningful works and be an audience of one for the art.

Developing a Thoughtful Approach

Developing a Thoughtful Approach

to Creating

However, if artists seek to share their work with viewers and potentially build careers in the world of art, it is important to understand that intentionality in making our work helps rather than hinders the creative process. Thinking critically about what we are creating can simplify the process in many ways and eliminate some of the frustration and wheel spinning that sometimes occur in the studio. Working in series, looking back at works that we have made, receiving critical input on our work, looking at work in galleries and museums, studying art history and particular artists to find a context for our own work, communicating in our Facebook art groups, and attending the annual Encaustic Conference are all ways in which intention and meaning can be developed and implemented.

Influences Affecting Intention

Rather than writing about my own work, I have asked Pro Wax members Lynda Ray and Timothy McDowell if I could include them in this article. I hadn’t realized before inviting them to participate that both artists found so much of the inspiration for their work in nature. What is so surprising and enlightening is the vast difference between their works even though both artists look to aspects of nature as a major influence.

Lynda Ray: Interaction of Patterns in Nature and Human-made Systems

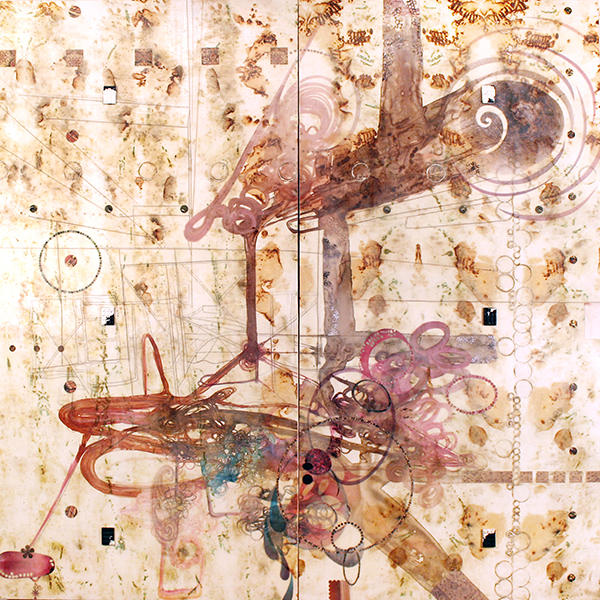

A Massachusetts native who now lives in Richmond, Virginia, Lynda Ray has established herself as a knowledgeable and well-qualified teacher of painting with encaustic in Virginia, California, Massachusetts and other parts of the country. At the Encaustic Conference she is known as the guru of textures. She works abstractly with drawing, frottage (rubbing to transfer textures), direct painting with encaustic and chine collé. She also creates larger works in oil, sometimes with cold wax.

Lynda’s work was included in both iterations of Swept Away: Translucence, Transparence, Transcendence in Contemporary Encaustic at the Cape Cod Museum of Art in Dennis, Massachusetts in 2013 and then at the Hunterdon Museum of Art in Clinton, New Jersey in 2014. Her painting, Fracture, was featured on the cover of the Hunterdon catalog, and her work, Landmark, was selected for the cover of the catalog of The Elephant in the Room: Contemporary Encaustic Works at Laconia Gallery in Boston in 2013.

When we were both at Massachusetts College of Art as returning students majoring in painting in the BFA program, Lynda and I became friends; we reconnected when we met at the Encaustic Conference decades later. The work we had each created during our years apart was parallel in many ways: emphasis on physicality, inclusion of found materials, love of pattern, geometry, texture, and strong emphasis on color. Despite this broad similarity, our work was inspired by entirely different sources.

In an online interview with Julie Karabenick of Geoform, Lynda said that her work was influenced by patterns in nature and by human-made, architectural elements. She also said that her work was experimental and intuitive.

Nancy Natale: Lynda, please expand on these seemingly different descriptions of why you make your work.

Lynda Ray: I work in the studio with a general concept of the visual idea I want to express. I engage with the materials and gradually the work comes into focus. I work intuitively responding to the colors, space, and marks that begin to form. Once there’s enough happening, it starts to become clear, and I organize the direction I want to take as I work towards the resolution of the work.

Many other secondary incidents happen as I paint that enrich the main direction and later may inform other works. I work back and forth between applying the paint and looking. Sometimes I photograph the work and/or move it to another location to see it in another context.

NN: Are your recent encaustic pieces with built-up texture and overlays of Asian paper still based on patterns from nature?

LR: Yes, I have a general concept which is based on my environment and asks the question of my relationship with the land. This idea came about after many years of looking, thinking, building/sculpting, and painting. I extracted from my environment colors, shapes, textures, and patterns that I felt had a history or story. This has been the consistent theme and interest most of my painting life.

NN: Would you say that when you use frottage to find texture in your previous work, you have become your own reference and personal environment?

LR: More recently I have used Asian paper to capture the surfaces of my sculptures or of found materials to make rubbings or frottage. I stash those Asian paper pieces into my flat files and use them as needed for my more recent work.

LR: More recently I have used Asian paper to capture the surfaces of my sculptures or of found materials to make rubbings or frottage. I stash those Asian paper pieces into my flat files and use them as needed for my more recent work.

I am always looking.

I think about time as expressed in layers, like a multiple-exposure photograph with each new century or event covering over the past but still leaving it somewhat visible. How can I express that in paint? That was and is my challenge.

The sense of building a work through layering can especially be achieved with encaustic painting through scraping back to earlier layers or showing the buildup of paint on a work’s surface or edges. The end result allows multiple moments to appear at once, as if one is looking through peeled back layers to reveal earlier stages of development.

NN: Do you care if the meaning viewers find in your work is not what you intended?

LR: I am hoping to express a universal idea. The work does not have a didactic intent. The best work would be capable of connecting with many experiences of the viewer. It is like experiencing music, without words.

Lynda Ray’s website: http://www.lyndarayart.com/

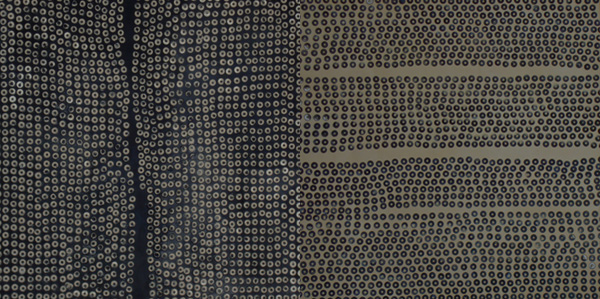

Timothy McDowell: Exploring Images and Systems Within Nature

Originally from Texas, Timothy McDowell received his MFA from the University of Arizona in 1981. He has been a professor of printmaking and drawing at Connecticut College in New London for more than 30 years. For the past 20 years he has been making paintings, prints, and works on paper in encaustic and oil. He has shown widely and his work has been acquired by many major private, corporate, and museum collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art Print and Drawing Collection, the New Mexico Museum of Art, and the University of Iowa Museum of Art.

Timothy’s recent work, Dry Planet, is included in the exhibition Organic to Geometric: Investigations in Structure and Surface at Endicott College, Beverly, Mass., January 20 – March 20, 2015, as well as in the catalog of the exhibition. Works such as this depict what I interpreted as a damaged natural world in danger of disappearing altogether because of environmental damage.

NN: Is my interpretation of your work what you had intended, Timothy?

Timothy McDowell: Your reading of the content is very close to my intention. It is an arid place, the structures are imagined, some future devices are functioning in some possibly futile way to collect moisture. The whole painting is about humanity’s attempt to regulate nature through technology, after ruining nature’s balance. It is a statement about how we disrupt balance and then try to correct it with science but rarely use the science to avoid imbalance.

NN: What is the meaning of the varied content and palette in images shown in the oil painting gallery of your website?

TM: The paintings shown in my oil painting gallery span four to five years of work, so my palette and subject changed over that span of time, even though all the work falls under the heading of exploration of nature and natural studies. I really try not to duplicate a painting once it exists. I try to make each painting an investigation with paint and subject in an attempt to understand the world around me. The whole process is one of visual research. If I don’t fully understand something or I am trying to learn more about something, painting it will help me know it better.

You mention one painting, Symbiotic Relationship, (I think you call it Day of the Locust, which I like!) and again, close enough on intention to satisfy me. This painting is about the interconnections of agriculture and nature: there is a mule, some oats, tobacco and, of course, the big grasshopper. All are in some way under the management of humans, either directly or not, naturally occurring or not, but nonetheless interconnected as a dark narrative.

NN: What I get from these paintings is a feeling of confused profusion or some portrayal of the extreme variety of things being displayed for some reason. Are these things that are disappearing; things that might disappear?

TM: These works were from an exhibition in 2010 at Marcia Wood Gallery titled Kingdom Come. The overall influence was my reading of accounts by early naturalists such as William Bartram, who explored Florida in the 18th Century. I was struck by the fact that a few of his discoveries were already extinct by the end of his own life.

Visually, I was also influenced by the documentation through rendering of many of the plants and animals catalogued during those explorations. Those influences combined with more contemporary thoughts on chaos and nature and evolution, which led to an imperceptible order inside the compositions. Nature always has order, but sometimes, because of its complexity, we can’t perceive it.

I also incorporated a sense of nostalgia through the color palette, the substrate (many are painted on the back side of National Geographic maps), and the subject matter. There are animals depicted that are becoming more and more rare but are placed within an image of profuse layers to suggest a diaspora of species in the animal kingdom. From profusion to extinction was the commentary.

Timothy McDowell, Wings to Steam, 2012, encaustic on paper (National Geographic map verso side) over canvas, 20” x 16”

NN: Does the variation in your palette reflect your emotional involvement in the paintings?

TM: These works, and I guess every painting I have ever done, are a reflection on my emotional involvement. I believe I am emotionally involved in painting: the act of painting, the history of painting, and maybe even the slowness of painting. It is a lifetime involvement which progresses at a pace that can’t be hurried. The time in the studio is the process; process is not the medium or the materials used. Of course I am both intellectually and emotionally involved with the content. Otherwise I would be more of a non-figurative painter and more involved with color and form as an intellectual exercise. We are filters and sometimes influences come without conscious awareness, so work changes gradually and doesn’t become apparently different until viewed as a comparative history of detail.

Timothy McDowell’s website: http://timothymcdowell.4ormat.com/

Developing a Signature Style by Working With Intention

Both Lynda Ray and Timothy McDowell very generously let us look into their processes. They describe a way of working that is at once intentional and intuitive. Within their own general framework of interest, each has left room for exploration and discovery, making each piece unique but still within the range of personal interests. Each artist has a signature style, or what might now be called a brand, that makes his or her work recognizable and personal. Instead of the beginning artist’s misperception that intention is a straightjacket of conformity holding back invention and surprise, we see that working with intention guides these artists on their creative paths.