How does a curated show differ from an invitational? What is the mission of an academic gallery? When are you ready to show? How do you price your work? Has anyone seen ArtZilla? The Saturday Morning Panel at this year’s International Encaustic Conference answered those questions and more.

BY JOANNE MATTERA

For Professional Practices: The Big Picture! I invited a stellar group of six artist-hyphenates

(-curator, -dealer, -professor, -ethicist) to talk with me about career issues. Miles Conrad, Fanne Fernow, Wendy Haas, Timothy McDowell, Jane Allen Nodine, and Carol Pelletier came with impressive resumes and a wealth of practical information. What follows is a synopsis of our nearly three-hour discussion.

Your Exhibition Options: Juried, Curated, Organized, Invitational

We started with the building blocks of a resume: exhibitions. For artists who are not gallery represented—and even for some who are—it’s important to understand how various kinds of shows help artists achieve visibility.

. As all the panelists noted, the juried show is the best and easiest way for an artist to build a resume. Work is selected by a juror—usually a dealer, curator, or critic—who is named in a prospectus. A well-selected show reflects favorably on all involved. Juried shows are typically held by non-profit entities, and there’s typically a fee to enter. For artists working in encaustic, juried shows offer a way of creating visibility within the community as well as a springboard to show beyond it.

Thinking about entering a juried show? “Pick and choose wisely because they can be costly to your wallet and your work,” said Jane Allen Nodine, director of the Curtis R. Harley Gallery at the University of South Carolina Upstate. She offered these considerations:

.Calculate first what will it cost you in work prep, entry fees and shipping, then clarify, what do you expect to get out of this exhibit?

.Do your homework: What is the venue, who is the sponsor, and especially, who is the judge?

.Will the possibility of this exhibit give you exposure to galleries, curators and collectors?

.Are there significant cash awards, a printed or online catalog, or the possibility of a future solo exhibition?

.Will your work be professionally presented and carefully managed in the process?

. The curated show is an exhibition in which artists are selected by a curator, whether she works for a museum or gallery, or independently, or is an artist or art historian expanding her practice by conceptualizing and realizing a thematic vision. There is no entry fee; indeed, you may not even know you’re being considered until the invitation arrives. A curated show is validation that your work has been sought out to become part of a larger discourse.

For the curator, it’s an opportunity to give physical form to a vision with and from artists’ work, noted Carol Pelletier, who curated the recent exhibition, Organic to Geometric: Investigations in Structure and Surface at Endicott College in Beverly, Massachusetts, where she is also chair of the Fine Arts department.

. The organized show gave pause to Wendy Haas, founder of the Cervini Haas Gallery in Scottsdale, Arizona, now an independent dealer and curator based in Chicago. “How should I describe this?” she mused. Ultimately both she and Miles Conrad, owner/director of Conrad Wilde Gallery in Tucson, acknowledged that like a curated show, selections are made by a curatorial entity working with a thematic idea, but that the exact selection of works may be left up to the invited artists, or juried from artist submissions, or both. Organized shows take place at galleries of all kinds.

. For an invitational show, a dealer or exhibition organizer asks particular artists to participate, usually around a theme. Said Haas, “I’ll often include some artists outside those already represented [by my gallery], as it gives both of us an introduction to working with each other. “

What’s the difference between a curated show and an invitational? Typically it’s the element of trying out a new artist or broadening an exhibition roster, as Haas suggested by her comment.

Your Gallery Options: Non-profit, Academic, Commercial, Co-op, and More

All galleries are not alike, and understanding their differences can help you decide how to approach them—or be approached by them.

. The mission of a non-profit gallery is to serve its community. It may sell work but it typically derives income from other sources, such as grants, fundraising, and donations. It is a good place for emerging artists to start their careers, or for seasoned artists to show experimental work, said Nodine, because the focus is on showing rather than selling.

Unlike  commercial galleries, non-profits don’t work with a roster of gallery artists so the potential for showing is higher, particularly if the mission is to engage the community by soliciting proposals or reviewing artists’ portfolios. Not every professional artist makes a living selling art (some survive on grants and residencies), so this type of gallery provides good visibility.

commercial galleries, non-profits don’t work with a roster of gallery artists so the potential for showing is higher, particularly if the mission is to engage the community by soliciting proposals or reviewing artists’ portfolios. Not every professional artist makes a living selling art (some survive on grants and residencies), so this type of gallery provides good visibility.

. The academic gallery serves artists similarly, since showing rather than selling is the priority. But, noted Pelletier, the academic gallery has a specific audience: its own academic community.

“If you are proposing a show, know that many of the academic galleries have planned exhibits one to two years out. Contact the chair of the department to see how your proposal fits into the curriculum,” said Pelletier. She added that artists whose proposals are accepted, or who are invited to show, may also be asked to give a talk or demonstration to the institution’s students, and typically an honorarium will be offered. (If it’s not, request one.)

. A commercial gallery is in the business of selling art. Artist and dealer are in a business relationship. A gallery-represented artist can reasonably expect to have a solo show every two or three years. Timothy McDowell, who has been gallery represented for the length of his long career, noted the needs of artists and dealers may change over time, so it’s not enough to secure gallery representation but to understand the dynamics of the relationship.

“As artists gain recognition and experience, their gallery representation may change from the local or regional gallery to one with a national or even international reputation,” McDowell said. Dealers, too, are looking to trade up, and some may drop artists with lesser profiles for those with greater art world visibility. In short, it’s hard work to get into a gallery and even harder work to remain there.

. Everyone on the panel spoke negatively about the so-called vanity galleries, those scurrilous businesses that troll for artists, offering group and solo shows for a steep price. Nodine said it most clearly: “Do not pay to play.”

. The one exception to paying would be co-op galleries, in which artists are juried into an existing artist-run gallery structure. Yes, artists pay a monthly fee to cover rent and other costs, but they are largely free to show what they wish and they receive a larger percent of sales, often as high at 80 percent. Our panelists noted that the co-op concept has an almost 100 year history and has given many artists their first opportunities to exhibit. This option got a thumbs-up all around.

Changing the Game: Do-it-Yourself

As our gallerists noted in conversation, there are never enough gallery slots for the number of practic ing artists. But while gallery representation may not be possible for everyone, Miles Conrad was clear in saying that every artist working now has options that would not have been possible even 15 years ago. “With the advent of the Internet, we’ve seen a huge upsurge in the DIY ethos,” he sai. “We can now publish our own websites along with our own writing, videos and tutorials. Printing has now been democratized with postcards, brochures and print-on-demand catalogs. We now send bulk electronic newsletters, sidestepping costly printed mailings. All of these activities are game changers for artists.”

ing artists. But while gallery representation may not be possible for everyone, Miles Conrad was clear in saying that every artist working now has options that would not have been possible even 15 years ago. “With the advent of the Internet, we’ve seen a huge upsurge in the DIY ethos,” he sai. “We can now publish our own websites along with our own writing, videos and tutorials. Printing has now been democratized with postcards, brochures and print-on-demand catalogs. We now send bulk electronic newsletters, sidestepping costly printed mailings. All of these activities are game changers for artists.”

. Open studios are ever more sophisticated, and both sales and connections are made. Fanne Fernow, who has often participated in juried Open Studios, attested to their value. “They are great for artists at all levels,” she said. Her reasons:

. You see people experiencing your work

. You get to practice talking out loud about it

. You’re basically curating your own solo show. You get to select work and hang the show. How does it read? Is it cohesive?

. You also make signs, labels and graphics. You learn to promote. It’s a really great way to gain experience.

. Pop-Up Galleries are artist-generated events that take place in apartments, vacant store fronts, and, well, let me share Conrad’s story: “There was a local undergraduate art student in Tucson who had one of those moving pods delivered right across the street from Gallery Row during one of the Art Walk events. She painted the inside white and hung a small but well curated group show. She ran clamp lights powered by a rented generator and hired a DJ. It was such a fun and refreshing event that she drew huge crowds from the mainstream galleries. It was the only time in my gallery’s history that I left one of our own receptions to wander out looking at something else!”

Know When You’re Ready to Show

“Showing your work is a natural step after having made something that you’re pleased with or proud of. Showing ranges from having an open studio to being exhibited by a gallery or museum,” said McDowell.

From a practical standpoint, Hass said that being ready means having “a consistent body of work, a sense of where you are in your career, and an opinion on your pricing.” From an emotional standpoint, McDowell felt that being ready to show means developing the ability to face rejection. “Being held responsible for your work and managing the huge range of viewer reactions requires a level of maturity. This comes with the territory,” he said.

Haas suggested this way to proceed: “Before you approach a dealer or curator, I’d recommend building your resume with juried shows and some of the more ‘grass roots’ options to gain both exhibition experience and a sales history.”

Then there are the other hats you wear. “After mastering your studio practice, be ready to master the requirements of a small business,” said McDowell. Contracts, artist statements, consignment forms, work ethics and consistency, presentation, craftsmanship are just some of what you need to be capable of handling— and handling well— prior to and after showing the work. What good is it to arrive at an artistic level of accomplishment only to fail at the practical components of going public? “

Then there are the other hats you wear. “After mastering your studio practice, be ready to master the requirements of a small business,” said McDowell. Contracts, artist statements, consignment forms, work ethics and consistency, presentation, craftsmanship are just some of what you need to be capable of handling— and handling well— prior to and after showing the work. What good is it to arrive at an artistic level of accomplishment only to fail at the practical components of going public? “

Pricing Your Work

When you’re gallery represented, the selling price is something you and your dealer set together since you will each take fifty percent. It’s not the dealer taking half of your hard-earned money, as so many artists mistakenly see it, but rather you and your dealer each getting what you feel you need to get for the work—mediated, of course, by what the market will bear. Emerging and/or unrepresented artists have a harder time with pricing, which these comments may help to clarify:

. McDowell has a per-square-inch system that allows for consistency when paintings are of many various sizes.

. Others artists (I am one) work with a fairly limited number of sizes and have developed a pricing system, nudged upward over the years, based on those specific sizes.

. I stepped out of my role as moderator to add to the conversation. When I taught Professional Practices at Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, I had students go around to the galleries to research the price of a particular size painting, one relating to the general size range in which they worked. Of course the prices from artist to artist and gallery to gallery varied wildly, but what the students came to understand from studying the available resumes was that exhibition history (museum, solo, and curated shows), plus reviews, grants and other distinctions, were essential elements in determining an artist’s prices. Selling history is another factor. And like it or not, a well-known artist can command a higher price, just as a high-profile gallery can command higher prices for its artists.

. McDowell, Conrad and Haas all voiced some version of this idea: Be consistent in your pricing, so that the work of a particular size, whether sold out of your studio, or at a gallery anywhere, costs the same amount. The internet allows collectors to comparison shop—and dealers to check—so across-the-board uniformity is in your best interest.

. McDowell, Conrad and Haas all voiced some version of this idea: Be consistent in your pricing, so that the work of a particular size, whether sold out of your studio, or at a gallery anywhere, costs the same amount. The internet allows collectors to comparison shop—and dealers to check—so across-the-board uniformity is in your best interest.

. Haas clarified consistency with this: “Maybe you’ll have a few different series that lend themselves to pricing variations due to the technique or materials used. That’s fine, but make sure the dealer can easily convey to a prospective client the reasons for differences in price.”

. McDowell added, “Your prices can go up, but they can’t come down.” He noted that as you move up in the gallery hierarchy and your prices get set accordingly higher, if you wish to remain loyal to the smaller galleries you started with, you may need to show scaled-down work at a price those galleries can sell, or create a series specifically for them.

. “Don’t sell the work at a price so low that you regret having sold it,” said Pelletier, who has seen this happen with students. Neither should you price your work so high that is has no chance of selling.

. I’d add one more thought here: If you are consistently the lowest-priced artist in a show, raise your prices. And if you are consistently the highest priced, then start showing in venues that better reflect what you feel is the value of your work.

The Artist/Dealer Partnership

When I was in art school, the prevailing idea was, “The dealer is your enemy.” What awful and misleading information to give to students! The artists and dealers on our panel had a much more holistic idea about what it means to work together.

. “The artist/dealer relationship is both a personal and business partnership,” said Haas. “Trust is crucial. Neither the artist nor the dealer wants to work with someone who will operate behind the other’s back.”

. And what about the gallery you start out with? Here’s McDowell: “The smaller gallery relationship may deserve some loyalty for having sold your work for years, providing the venue from which your reputation grew. There is room for both. Work [scale, type of project] can be adjusted to maintain the early relationship. Branching out to bigger and hopefully better opportunities does not necessarily mean that bridges be burned.”

. Here’s something that many artist don’t realize: Most dealers do not come from wealth, and many struggle financially just as artists do. They are in the business of selling art for the same reason we are in the business of making it: Neither can imagine a life without it.

Being a Good Art World Citizen

If we’d had another hour, we would have talked more about some of the bêtes noirs in our community: appropriating images and ideas, stepping on toes, inventing “referrals” to get an in with a dealer, and the way situations often blow up out of proportion, especially on social media. I asked Fernow, the only artist on our panel—perhaps in the entire encaustic community—who has a divinity school background, to address some of these issues in general terms. Here is her response:

If we’d had another hour, we would have talked more about some of the bêtes noirs in our community: appropriating images and ideas, stepping on toes, inventing “referrals” to get an in with a dealer, and the way situations often blow up out of proportion, especially on social media. I asked Fernow, the only artist on our panel—perhaps in the entire encaustic community—who has a divinity school background, to address some of these issues in general terms. Here is her response:

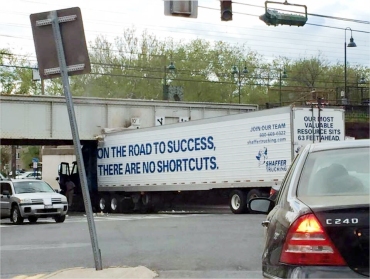

“If you reside in some sort of artist community, either housing or studio space, it is good to find ways to work together. There is a woman with a studio in the complex where I have mine. She is a Buddhist nun. But when it comes time for an open studio event, she turns into ArtZilla. She wants the most wall space in the hallways. She wants to place things in the hallways that will enhance the journey into her space, not yours. She must have bigger signs than yours. It is not fun to work with her.

“I have known more than one ArtZilla over the years,” Fernow continued. “They are the artists who don’t want to do their fair share of the work, the artists who think they are the only one with something to offer, the artists who are fine with not paying their own way. When given the great opportunity to work with and learn from others, please be a good citizen of your community and leave ArtZilla at the door.”

Fernow concluded our discussion with these thoughts:

“A lot of people will do anything to have their art be seen. Understand the origin of your ideas and why you are making that particular work. Ask yourself if the work is original and what it means. Do you have a chance to help someone with less experience than you? Do you have a chance to invite others to follow you on your path? Do you work and/or play well with others? Can you carry your own weight? Sometimes the desire to have your work seen and recognized blinds you to anything or anyone else. Please think seriously about your behavior. If you have never considered your ethics, please do it now.”

. . . . . . . . . .

–Joanne Mattera is the founder/director of the International Encaustic Conference. She could not have completed this piece without the help of the panelists, who verified and clarified their comments. Read more about the panelists here.

Want to know more about the Saturday Morning Panels? In previous years we’ve discussed A History of Contemporary Encaustic (2014); Raising the Bar: Encaustic in our Practice (2013); Igniting the Spark, Fanning the Flames: Creativity in Our Practice (2012); Mastering Media (2011); Making a Career in Encaustic (2010); Conservators on Conservation (2009); How the Press Views Encaustic (2008); and the very first year: Encaustic: State of the Art (2007). (More year-by-year info can be found in A Brief History of the Encaustic Conference.)

Thank you for great piece of information. Would love to see more posts like this. I am as an artist, interested in how to find a dealer or a gallery representation (And I mean a private business kind of gallery). Would love to hear more.

Thank you.

Rinat Goren