With Lorrie Fredette

By Nancy Natale

Above the cloud view of The Great Silence at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, Dennis, Massachusetts, 2011

I remember seeing Lorrie Fredette’s installation, The Great Silence, in the main gallery at the Cape Cod Museum of Art in 2011. It consisted of a massive 36-foot-long canopy of wax-painted muslin forms suspended from a metal grid under the room’s huge skylight. The light from above illuminated them and emphasized their hollow, irregular shapes. In the room’s air currents, individual elements drifted slowly and silently in almost imperceptible movements, small vessels within the vast cloud formation. Above the canopy, a glistening veil of nylon lines supported individual elements below at slightly varying heights.

Installation view of The Great Silence, Cape Cod Museum of Art, 6 feet 2 inches x 36 feet 9 inches x 5 feet 8 inches, suspended 8 feet 6 inches above the floor

What was the meaning behind this installation, I wondered. Was it all about the beauty of these light-filled objects or did the artist intend more with this powerful and labor-intensive work? My interview with Lorrie Fredette allowed me to explore the meaning and method of her extraordinary work.

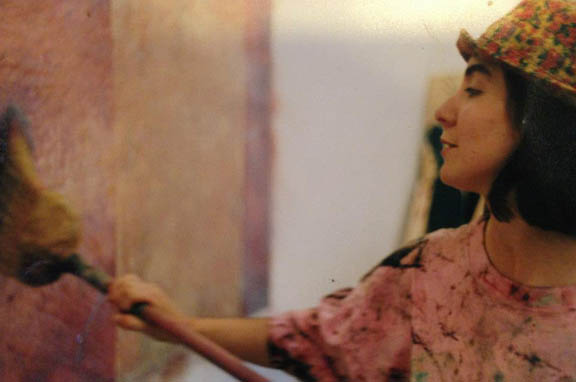

Studio portrait of Lorrie Fredette

If you are unfamiliar with Lorrie Fredette’s work, it helps to know that she creates site-specific installations, sculptures, and drawings inspired by medical and environmental stories. At the core of all of her work is her interest in repetition, many small parts coming together to create a larger whole.

Nancy Natale: Do you have a name for the wax-covered muslin pieces that you make?

Lorrie Fredette: Though I most often refer to the pieces as pods or elements, they have also been referred to as components, pieces, units, and ingredients. As a single member, each is important. However, it is their aggregation that has the most visual forcefulness.

Identifying names for the installed collective whole varies by concept, site and assemblage. For example, I refer to The Great Silence, a site-responsive installation for the Cape Cod Museum of Art, as an undulating canopy. Complex Interplay, a site-responsive installation, for the Islip Art Museum, is referred to as clusters.

NN: Would you describe your process of making these elements?

LF: I handcraft each element from the armature to the painting. On occasion, I hire assistants to help with aspects of the making.

A brass wire armature is hand formed and soldered. Though there is no mold or physical pattern, each frame is created with a specified length of wire in order to retain some size consistency.

Closeup showing variety of pod shapes as well as line and shadow, Situational Variables, Herron School of Art + Design, Indianapolis, Indiana, 2016

Unbleached cotton muslin is fitted to each frame and sewn by hand, assuring a tight painting surface. It is in this part of the making that I bring in studio support because it is the most time consuming part of the process.

Every pod is painted individually with a minimum of five coats of beeswax and tree resin (encaustic medium). Often the painting layers exceed nine but five is the absolute minimum density.

NN: How do you decide on the shapes and the variety of shapes in an installation?

LF: The variety of shapes and sizes for each installation is determined by multiple factors and these considerations are richly intertwined. My work is activated though research, which often includes geographical area of the hosting venue; who is the hosting venue; current and historical news of the area including environmental, medical, social, and political (these are often already intertwined); microscopic imagery of bacteria and viruses; the measurable impact of a disease (morbidity and mortality, food supply, as well as other economic losses); and the physical attributes (square footage, height and special features) of the space.

By collecting, comprehending and culling through the data, the facts and the falsehoods, shapes, sizes and configurations come into focus. One aspect of the process is to create renderings reflecting my interpretations.

NN: How closely does your scientific research influence the objects that you make and the form of the installations?

LF: It would be false for me to suggest the research doesn’t hold some authority. However, the foundation of my making is drawing. I attempt to translate the language-based research into drawings and any image findings into my own handwork.

For example, when I create the very first sketch of a microscopic image such as smallpox virus, the drawing is as literal as I possibly can make it. The sketching of this one particular finding doesn’t stop there. It’s actually the beginning of my visual note taking. The drawing process is repeated with only the previous drawing as my source. Because of this process, I’ve created my own evolution over this one image; drawing #20 of the smallpox virus shows noteworthy differences from drawing #1 and from drawing #50. And, yes, there can easily be 50 drawings. I see the relationship of each visual translation to its predecessor as linear, orderly, and progressive, but should you view a sampling of these drawings, you might not see them as sequential.

NN: How much of your research do you want to share with your audience?

LF: If any of the research is to be shared, I’m only interested in it appearing as statements, press releases, and conversations. I’m interested in creating spaces visitors that find approachable, inviting and, dare I say it, beautiful. Because the work is boldly attractive, I see it as a conscious lure ushering each person into the space and toward, into, and under the installation. Once I have them involved, many people will seek out the supporting statement. So, it’s the art first, the science second.

Implementation of Adaptation, Garrison Art Center, Garrison, New York, 2013, 6 feet 1 inch x 36 feet x 12 feet, suspended 40 inches above the floor

I want to be clear that I’m not a scientist. I’m an artist interested in science. My research is motivated by my interest, and I am mindful that it can become convoluted. I’d never suggest the majority of my research findings as facts, though when I write about the work for venues or am speaking about the work, I make sure I have the recent facts to share.

However, I’ve noticed a recent pattern has developed within the arrangement of the installations. It is the number of individual elements. They now typically reference some factual statistic. For example, the installation Implementation of Adaptation included 574 individual elements referencing the number of reported outbreaks by the New York State Department of Health for yellow fever, dengue fever, malaria, and West Nile virus during a specific range of time.

While I do wish for people to consider the science at some point, I’d be making different work if the science was the most important aspect or even equally important as the art.

NN: Do you consider yourself a sculptor who does installations or an installation artist who installs objects? That is, how important are the individual objects that you make? Are you thinking of them as a group of multiples or as individual objects that you combine together?

LF: I believe my response is going to surprise you. I consider myself a painter. I paint portraits and landscapes — molecular portraits and the landscape of the body. I simply manifest them as larger dimensional objects intervening in architecturally defined spaces.

The individual object and the whole have equal importance. There are several parallels we can reference. Medically, one person sneezing will eject and distribute millions of fluid droplets covering a room in seconds and hovering in the air for some time. A second reference is the importance of an individual vote. It is in their totality that political determinations are made, but without the individual there is no aggregation.

NN: What influences the installation height for hanging work? (i.e. I’m thinking of The Great Silence installed at three different heights in three different locations)

LF: Simply put, it’s the level of engagement I’m interested in obtaining from the visitor.

The Great Silence, Morean Art Center, St. Petersburg, Florida, 2012, 6 feet 2 inches x 16 feet 4 inches x 5 feet 8 inches, suspended 40 inches above the floor

Each venue offers a complex and unique set of variables. As a choreographer–and I do actively participate in this role—my attention turns toward encounter. The study of disease transmission (such as person to person or airborne), the internal traffic patterns of the hosting venue and the gallery’s architectural features are a few components I use to inform the hanging height.

You’ve mentioned The Great Silence. The installation was specifically created for The Cape Cod Museum of Art. The best presentation for the work was creating an undulating canopy for people to walk under because it would be the most inviting in this space. The gallery is largish and the majority of shows are painting, drawing, and other work on the walls. Obviously, I was directing and moving people to the middle of the room. The installation’s pod-like forms were suspended just above visitors’ heads by 24 to 36 inches, depending on the visitor’s height.

The Great Silence, Bank of America Headquarters, Charlotte, North Carolina, 2012, 6 feet 2 inches x 16 feet 4 inches x 5 feet 8 inches, suspended approximately 24 feet above the first floor

One of the other locations for The Great Silence was at the Bank of America. It was an abbreviated version suspended at the second-story level in their atrium. The idea was to provide a distant viewing so that no matter the vantage point of viewers walking under it, in the ground-floor lobby or in the perimeter of the second story corridor, they would always be at a safe distance from the work.

On a technical note, I always find a work-around to any structural concerns. It’s an opportunity to expand my abilities and that of my installation crew.

NN: How much does the architecture of the gallery influence your installation? I’m thinking of the comparison between Complex Interplay at the Islip Museum and Imperfect Distribution at the Hunterdon Museum of Art – neither one in a white box gallery. To my eye there were some similarities in that the installations seemed particularly graceful and curving. Of course I wouldn’t use the word “decorative,” but they did not seem like they referred to scientific research. How wrong am I?

LF: Islip and Hunterdon are environments where seeing the work in person has a stronger impact. The photographers I hire are very good but they cannot translate the experience and can’t replace the actual environment.

Imperfect Distribution, Hunterdon Art Museum, Clinton, New Jersey, 2015, 8 feet 6 inches x 21 feet 2 inches x 35 feet

The title I give each installation is to provide an entry point for the viewer. I’ll reference just one of the installations to respond.

Complex Interplay, exhibited at the Islip Art Museum, references the space— the building as body and host for the work. There is a “complex interplay” between a virus and its victim including where it enters the body, the type of cells in which it can reproduce and whether it can then escape to reach another human.

The Islip Art Museum’s main artery hosted Complex Interplay. I was thinking of the building as a vessel that acts as a container of people and objects. Within this repository, corridors serve as a distribution vehicle offering people a pathway to their intended (or not so intended) destinations.

Complex Interplay, Islip Art Museum, East Islip, New York, 2014, 14 feet x 9 feet 8 inches x 34 feet 6 inches

Using these symbolic references of vessel and corridor, the architecture serves as “host” of an unknown contagion where the interchange of virus (the art) and victim (the building) reproduce and escape to reach its next target (the viewer).

The Islip Art Museum installation didn’t have an “it’s this disease” identity; it did have “this is how disease can spread.”

NN: The porcelain installation, Proper Limits, that you did at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey in 2015 and at Rutgers in 2016 seemed to move your work in a different direction because of the material that you used, the way it was installed, and the sound component. You created a whole environment for the work. It had a really creepy feel and I thought it evoked more of an emotional response than your other installations. Would you comment on this? And can we expect more immersive installations like it?

LF: The “creepy” response was certainly intentional. Thank you. I take it as a compliment.

I have a background in theater. I worked as a Properties Artisan in regional repertory a few years after graduating from college. In this theater, the production staff worked closely with the director and the designers. Because of this, I gleaned my initial knowledge of blocking (space usage), interplay with objects (props), lighting, and sound.

Therefore, each installation is all encompassing, though I believe the Visual Art Center of New Jersey provided a unique experience because of the space it offered. The gallery size, the low drop-ceiling, as well as having just one way to enter or leave the gallery enhanced viewers’ visceral response. The gallery truly expressed itself as a habitat where these serpentine-like forms claimed ownership.

Proper Limits, Visual Art Center of New Jersey, Summit, New Jersey, 2015, 18 feet 3.5 inches x 17 feet 10.5 inches x 8 feet

There were a number of alterations or enhancements made to the space to elicit reactions in the installation. The floor was transformed from blonde wood to white linoleum and that change was critical. It produced the necessary experience of separation from the “outside world.” More than a third of the drop-ceiling tiles were changed out, allowing me to introduce tiles with the porcelain elements already attached.

The materials I select for my work are always in service to the concept and not just my personal interest. In choosing porcelain for the elements of Proper Limits, a few of my reasons were because it is “of the earth,” because the symbolically white color is associated with purity, and because the sheer number of components was not as immediately visible on the white gallery walls.

The introduction of sound in Proper Limits was used to push many visitors to their edge. It was a risk on my part (and that of the VACNJ) to show such a piece because a percentage of visitors refused to engage with the piece, meaning they would not enter the gallery. Of course, this was also a response I wanted. If you did enter the space and you were alone, you would hear a faint undertone. The sound associations were routed in facts associated with Lyme disease—neighborhood noises, rustling trees, wind sounds, and hospital noises. [You can view a video of the installation here.]

As I’ve grown and my knowledge expands, so does the way I present my work. Viewers most certainly may anticipate more saturated and involved experiences.

—————————————————————

Based in the Hudson River Valley in New York, Lorrie Fredette gravitates toward the iconography and material sensibility of the Postminimal Art Movement, specifically in dimensional form.

Lorrie Fredette’s next exhibition, Iterations, is a solo at the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville, in Jacksonville, Florida, opening April 8, 2017.

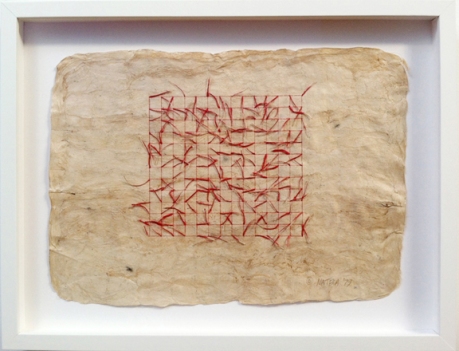

Yes, this is me in 1978 when I was drawing with thread on paper. I’d made my first encaustic painting 10 years earlier in art school but didn’t return to wax until the mid-Eighties

Yes, this is me in 1978 when I was drawing with thread on paper. I’d made my first encaustic painting 10 years earlier in art school but didn’t return to wax until the mid-Eighties

. . .

. . .

Anna Wagner-Ott I live in a place where the population is 1000 and I am the only one making non-representational art. I feel like an outsider. At this point, I have not found [an artistic] community where I live. On the other hand, I have attended the Conference and met like-minded individuals and continued conversations in the virtual world. I joined the Raising the Bar Facebook group, and feel connected with the world. I don’t feel isolated anymore. Each year in June, I connect [in person] with my Facebook friends and have lots of talks about art. It is amazing, really, that one can get a sense of community through emails and on Facebook. It is very important that I have a community of artists where I can express my ideas and share my work, even if those discussions are through the internet.

Anna Wagner-Ott I live in a place where the population is 1000 and I am the only one making non-representational art. I feel like an outsider. At this point, I have not found [an artistic] community where I live. On the other hand, I have attended the Conference and met like-minded individuals and continued conversations in the virtual world. I joined the Raising the Bar Facebook group, and feel connected with the world. I don’t feel isolated anymore. Each year in June, I connect [in person] with my Facebook friends and have lots of talks about art. It is amazing, really, that one can get a sense of community through emails and on Facebook. It is very important that I have a community of artists where I can express my ideas and share my work, even if those discussions are through the internet. Debra Claffey I serve on the board of an art group working for gender equity and connect with others over landcare and eco-sustainability.

Debra Claffey I serve on the board of an art group working for gender equity and connect with others over landcare and eco-sustainability. I’ve lived in places where I’ve been very involved in organizing shows and open studios, showing together with people, and working on arts councils. Those relationships were centered around projects or activities, rather than establishing bonds and sharing thoughts and views over long periods of time. While we are mainly focused on work in encaustic here in ProWax, we are not chained to that medium. We are also aware of and appreciative of artists and shows that have nothing to do with medium.

I’ve lived in places where I’ve been very involved in organizing shows and open studios, showing together with people, and working on arts councils. Those relationships were centered around projects or activities, rather than establishing bonds and sharing thoughts and views over long periods of time. While we are mainly focused on work in encaustic here in ProWax, we are not chained to that medium. We are also aware of and appreciative of artists and shows that have nothing to do with medium.